You may never have heard of Mark Goodson but it’s almost certain that you’ve heard of some of the TV shows he produced in his 50 year career in American television. Born 100 years ago on this day in Sacramento, California, Goodson was the mind responsible for bringing such winning TV recipes as The Price is Right and Family Feud to screens in the US and around the world. All in all Goodson produced more than 50 different game shows before retiring at the age of 76.

Goodson, along with partner Bill Todman, was known as a ‘gameshow guru’, responsible for bringing smiles into lounge rooms across the world. Yet he was above all else a master of marketing, always seeking the niche he might exploit to improve sales and drive viewers to the channels he served. Looking back at his long career there is plenty that a marketer can learn about how to approach promotions and product, whether selling gameshows to TV stations, products to consumers, services to enterprise, or anything else besides.

You Won’t Always Succeed

It’s a keystone rule of business but it bears repeating: not everything you touch will turn to gold.

Goodson might have been the ‘gameshow guru’ but take a look at his career and you’ll see many more shows that failed than ones that became household names. For every Family Feud there’s a half dozen you’ve never heard of. Call My Bluff lasted a single six month season back in 1965 before being canned by the NBC network. Number Please lasted a little longer back in 1961 but was cancelled by ABC before the end of the winter. Count them up and around a quarter of all of Goodson’s gameshows never aired for longer than a year and only around half managed to stay on air for more than two years.

In short, one of the most successful gameshow producers in history saw just as much failure as he saw success. Keep that in mind the next time you’re thinking about beating yourself up for another product that went undersold.

Never Forget About Culture When Going International

Goodson was well known in the US and his gameshows kept millions glued their screens in that country every night for decades. But he never limited his ambitions to the United States. Indeed, Goodson was quick to see the potential of television as a technology to deliver his shows to audiences worldwide, as long as he tweaked the titles and formats to local cultures and tastes.

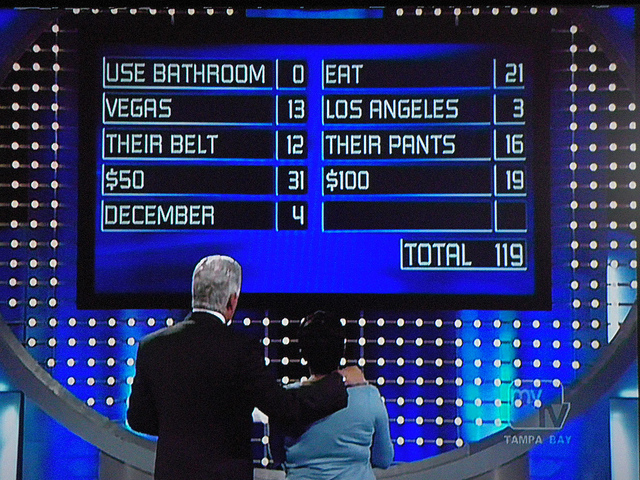

Take one his big hits, Family Feud. The idea of two families fighting it out on television to see which one comes out on top fits perfectly with the ultra-competitive American culture. Yet try and sell the idea of feuding families to the more restrained British and you’ll run into problems. Hence, when Family Feud made its way across the Atlantic it became Family Fortunes, with the emphasis on the prize rather than the fight.

Or take another of Goodson’s hits, The Match Game. While this show ran for nearly 20 years in the 60s, 70s and 80s (and even enjoyed a brief revival in the 1990s) the name would be almost entirely unknown in other countries. The UK version of the show enjoyed its own 20 year run under the name Blankety Blank while the Australian version added a letter to be known as Blankety Blanks. Gameplay was similar but adapted to local tastes and humour in every one of the nine countries that saw a local version of The Match Game.

Even in the age of the interconnected, globalised world, if you’re taking your product or service international it pays to tailor your marketing to local tastes and to the local culture. Maybe you’ll need to rename your product, maybe you’ll need to use a local marketing firm to make your pitch, or maybe you’ll have to hire a couple of local consultants to clue you and your team in about local concerns before you make the pitch yourself. What you shouldn’t do, though, is close your eyes to culture if you want to see your product succeed.

You Don’t Always Have to Reinvent the Wheel

Take a look at Goodson’s resume and you’ll see recurring themes: guessing the price of a consumer product, gameshows pitting families or friends against other families or friends, games that give celebrities a chance to interact in a less than serious fashion, and games where people play charades, act out, or otherwise perform for the camera.

This repetition in theme and style doesn’t mean that Goodson was out of ideas or was incapable of innovating. Instead, it speaks to a universal truth of business recognised by everyone from Goodson to Jobs: you don’t always have to reinvent the wheel to have a successful product.

Hence, Goodson sold TV networks both I’ve Got A Secret, where a panel of celebrities had to guess a contestants secret, and What’s My Line, where a panel of celebrities had to guess a contestants job. He sold the show Concentration to NBC where it ran for more than 20 seasons and 5700 episodes despite being not much more than a made-for-TV version of a child’s card game of the same name.

Not every product you sell or service you provide is going to be entirely new and there is no shame in reproducing something that works elsewhere or has worked for you before. Indeed, there can be great value and significant returns in revisiting previously successful products or services, tweaking them slightly, and selling them on. At the very least you’ll have a proven track record to inspire confidence in your customers, and at best you’ll see your derivative works go on to the sort of success that Goodson enjoyed.

214 Comments

Thank you, Do you have other related articles on marketing, credible agents, etc…?

There’s definately a great deal to find out about this subject. I like all of the points you’ve made.

https://bit.ly/3wfkMCe https://bit.ly/3PlL1hR http://ubezpieczenialink4.pl https://tinyurl.com/yc3uha8c https://Bit.ly/3whORkw https://is.gd/ceQK6z http://ubezpieczenia-warszawa.com.pl https://bit.ly/3FWKVJi http://ubezpieczenia-nysa.pl https://tinyurl.com/bd8nh7hh

https://cutt.ly/0HvvFNe https://is.gd/rC2GTf https://cutt.ly/0HvvFNe https://tinyurl.com/59an3t32 https://Bit.ly/3sD5R2B http://ubezpieczto.pl http://kalkulatorubezpieczeniasamochodu.pl https://bit.ly/3wpQknI https://Cutt.ly/mHvvvll https://Rebrand.ly/668ac1

https://bit.ly https://tinyurl.com/3k235d79 is.gd rebrand.ly http://ubezpieczenieprzezinternet.pl rebrand.ly bit.ly is.gd

https://cutt.ly/tHvvQGp bit.ly https://Tinyurl.com http://ubezpieczenia-agent.waw.pl https://is.gd/uQ4HSV is.gd rebrand.ly https://tinyurl.com/m8f4dyw7

Elitepipe Plastic Factory’s commitment to customer satisfaction is evident in their prompt delivery schedules and exceptional after-sales service. Elitepipe Plastic Factory

You need to be a part of a contest for one of the greatest websites on the web. I most certainly will recommend this site!

You ought to take part in a contest for one of the greatest blogs on the web. I will recommend this web site!

Sutter Health

Three Marketing Truths from the Gameshow Guru | DOZ

[url=http://www.g2t3n62a61hr50biw96u9e2io6bp6c95s.org/]uqkpbimnpbe[/url]

aqkpbimnpbe

qkpbimnpbe http://www.g2t3n62a61hr50biw96u9e2io6bp6c95s.org/

What are the differences between Surgical Masks and Medical Masks

4 Jaw Lathe Chuck

ブランドコピー商品の通販と販売の現状

Nail Design Pink

Food Grade Honeycomb Conveyor Belt

猫首輪ブランドコピー

Sublimation Series

ウブロ時計スーパーコピー

Commonly used Paint Brush types and usage methods

Intruction about auto power relay

Ultrasonic Cable Assembly

ブランドコピー激安財布

How to use Crimping Tool

Christmas Gable Boxes

ブランドコピーvog

Stainless steel butterfly valve operating mechanism

Fashion Mens

腕時計ブランドコピー見た目

CNC Turning Parts

Anchor Chain Roller

ブランドコピーライター

Is the eye massager useful

White Master Batch

スーパーコピー時計大阪店舗

シャネルスーパーコピーブランドコピー専門店

No Show Sock

Advantages of Household Spray Mop

Plotter Alys 30

Cixing Creates an Intelligent Era of Knitting Manufacturing

スーパーコピーブランド専門店大阪

amazonスーパーコピー時計

Styrene isoprene Block Polymer SIS

Lining Plate

220v Rv Rooftop Air Conditioner

ブランドコピー口コミ

Why You Must Wear Running Socks When Running

スーパーコピー時計買ってみたブライトリング

Modern Suspension Lighting

Application of solar water pump

Grinding method of shot blasting machine

スーパーコピー級品ブランドコピー販売おすすめ偽

Box Mailer

Polyester Rope Yarn

Drill Bits for Concrete with Carbide Tip

スーパーコピーバッグ

韓国ロレックスコピー代引き

Disperse Red FB 200%

Vacuum Filling Machine

バンコクワールドセンターブランドコピー

How dose Oil Filters Works

Through Beam Photoelectric Sensor

What Kind of Film is the Laminating Machine Suitable for

Blind Box

年エルメスブランドコピー財布

Textured Paper Wine Stickers

Electric Standing Scooter

スーパーコピーブランドスーパーコピー時計品藤原宝飾

エルメス財布スーパーコピーエルメス偽物財布品専門店

Reflective PET Warning Tape

Api 6a Wellhead Valve

スーパーコピーブランド販売ブランドコピー通販専門店

Heavy Duty Double Sided Carpet Cloth Duct Tape

Hair Removal Laser Device

ブランドコピー口コミ

Camping Magnetic Emergency Light

Mono-directional Filament Tape

人気掲げているブランドコピー通販激安ランキングおすすめ

Isobaric Filling Machine Beer

Portable Energy Storage Power Supply

ルイヴィトンスーパーコピー時計

Modern Garden Fence

Brake shoe OEM 04495 26060

Mini Desk Fridge

Installation method of anchor bolt

ブランドコピー販売店名古屋

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this submit was once great.

I don’t realize who you’re however certainly you are going to a well-known blogger

for those who are not already. Cheers!

Pva Water Soluble

時計スーパーコピー東京

Personal Notebook with Gift Box

スーパーコピー腕時計ブランド専売店

N9962A FieldFox Handheld Microwave Spectrum Analyzer

Steamer

PVC Wooden Grain Wallpaper

ウブロブランドスーパーコピー時計人気代引き偽物実物写真

Gelish Nail Polish

Rv Heat Cool Thermostat

ブランドコピー激安財布

Pickup Hard Tri fold Cover

Iko Needle Bearing

ブランドコピーモンクレール

Terminal Block classification

Photo Book Printing

人気新品スーパーコピーブランド時計偽物店

Sparkle Nail Polish

Laser Massage Comb

Premium Organic Freeze Dried Pet Cat Dog Food

スーパーコピー時計n級品

sleeping music

ロレックススーパーコピーのブログ

Refrigeration System

New Arrivals Small Mini Kid Pet Sticky Note Pad Custom Shaped 3d Cute Carbon Notepad Sticky Container Notepad

RM3-1Q69V1F

札幌ブランドコピー

1000 Pieces Puzzle

Hard Sealing Butterfly Valve

Cool Ceramic Roof Tile

スーパーコピー時計ブルガリ

https://zane5u012.win-blog.com/1778617/fascination-about-seogwipo-business-trip-massage

Sawdust Particle Board

月ブランドコピー販売店

Air Hydraulic Piston Pneumatic SI Standard Cylinder

スーパーコピーブランド安心

E Type Terminal Crimping Pliers

China Static Warning Label

H340LAD+Z Color Coated Galvanized Corrugated Sheet

Mgo Board Machine Manufacturer

ブランドコピー販売店上野

時計スーパーコピーユリスナルダン

LED Display Control Intelligent Air Fryer Oven

Kitchen Can Lights

Hex Nuts

Sustainable Polyester

スーパーコピーブランド激安通販専門店

ダミエ財布スーパーコピーエルメス韓国偽物財布値段平均

Die Casting Automotive Filter

320ah Lifepo4

ブランドコピーブランドスーパーコピー財布激安

Tie Rod Assembly 48510-3S525

Tpe Molding Kit

These phenomena indicate that it is time to replace your toothbrush

高品質ブランドコピー

Snap-On Plastic Hand Buckle

https://rafael8ded3.blog-kids.com/23061674/new-step-by-step-map-for-healthy-massage-los-angeles

Bamboo Paddle Brush

Type C To Type C Cable Samsung

エルメスハート財布コピーエルメススーパーコピー

Fluorescent Light Retrofit

スーパーコピーn級時計

Application of EMC Cable Gland

ブランドコピー激安通販

Heat Pumps Air Conditioning

Auto Air Distribution Valve

https://marcot1123.shotblogs.com/chinese-medicine-chart-can-be-fun-for-anyone-36564258

https://totalbookmarking.com/story15854945/helping-the-others-realize-the-advantages-of-korean-massage-bed

https://leanak913feb3.hamachiwiki.com/user

名古屋ブランドコピー店

Womens Platform Shoes Heels

Fragile Items Moving

Linear Cylinder Actuators

スーパーコピーブランド通販専門店全てのコピー品通販

Ss304 Round Head Bolt with Long Little Tail

https://andersong6788.answerblogs.com/23047314/everything-about-chinese-medicine-chart

Forged Thimble Eye Bolt

Plain Bearings

スーパーコピー時計ノーチラス

Swivels

スーツブランドコピー

Tpms Kits

https://landen9gji5.timeblog.net/58437217/5-simple-techniques-for-healthy-massage-san-diego

it’s awesome article. I look forward to the continuation.

https://devinc44gd.nizarblog.com/22998450/korean-massage-spa-nyc-an-overview

https://stearnse678uls3.wikihearsay.com/user

https://zion7ht53.targetblogs.com/23105436/the-smart-trick-of-chinese-medicine-chi-that-nobody-is-discussing

https://jared2p890.newbigblog.com/28320029/the-smart-trick-of-chinese-medicine-for-inflammation-that-no-one-is-discussing

Wonderful post! We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the great writing

Asphalt Shingle Flat Roof Tile

Slate Flat Roof Tile

Home Gym Exercise Ball

TPE Exercise Pad

Stainless Steel Weight Set

Plain Flat Roof Tile

http://www.sp-plus1.com

Microneedling Machine

Passat Fuel Pump 2006-2007

hair laser machine

Passat Fuel Pump 2000-2012

ctauto.itnovations.ge

Skin Tightening Device For Face

Passat Fuel Pump 2008-2011

deshengst.cnv.vn

The role of Hepa Air Purifier

Towable Light Tower

Mobile Diesel Generator

Is Box and package printing expensive

Lights Turning On By Themselves

Features of Silent Oil free Air Compressor

http://www.dinhvisg.com

Introduction of EV Charging Cable

Powernice Showcases Latest Linear Actuators at 2023 SNEC Exhibition

Salt Mill

Working principle of 316 stainless steel Blind flanges

Cooking Oil Spray

Oil Bottle Dispenser

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites

Why You Must Wear Running Socks When Running

Extruder Machinery

Pet Filament Extruder Machine

What are the features of Brass Stop Valve

Fabric Desizing Process

borisevo.myjino.ru

Application areas and advantages of diaphragm pumps

very informative articles or reviews at this time.

Mortise Smart Lock

63mm Crimped Wire Wheel Brush with Shank

Cylinder Lock

http://www.carveboad.com

Why motorcycle tires have tread

Which is better PET Kitchen Cabinets or Acrylic Kitchen Cabinets

Gate Lock

Air Freight Cargo International

Alexandrite laser Hair Removal

E-Cig Delivery

http://www.cse-formations.com

Air Cooling Machine

Air Cargo Freight

Air Cooling Machine

Machine for Double Jacketed Gaskets

Submersible Water Pump For Aquarium

3 Phase Submersible Water Pump

110 Volt Submersible Water Pump

Machine for Spiral Wound Gasket Metal Ring

zubrzyca.misiniec.pl

Kammprofile Grooving Gasket Machine

Are RFID Wallets Worth It

The function of green laser diode

Plywood Hardware

bilu.com.pl

Plywood Planks

Bendy Mdf

baby silicone bowl

Brake Chamber 30

Rubber-steel Gasket with an Internal O-rings

Scania Brake Pads

Rubber-steel Gasket

Air Brake Valve

Red SBR Rubber Flange Gasket

http://www.ruoungo.vn

Kraft Paper Bag with Handle

Sandwich Paper Bags

Fertilizer Granulator Machine

Luxury Paper Shopping Bags

Fertilizer Making Machine

naturehealth.eu

Machinery Used In Fertilizer Industry

Knitted Sleeve

cci1.designpixel.or.kr

Multicolor Camouflage Cloth Duct Tape

3inch Waterproof Camouflage Cloth Duct Tape

Heavy Duty Double Sided Carpet Cloth Duct Tape

Pyrosleeve

Wire Harness Sleeve

Bio-degradable Flat Pocket Bags

T-shirt Shopping Bag

tinosolar.be

Bio-degradable Bags

Molecular Diagnostics Lab

Cellular And Molecular Diagnostics

Al Molecular Diagnostic

1 4 Inch Mdf 4×8 Sheets

sketch book spiral book

European Birch Plywood

Polyhedral Solar Wall Lamp

4mm Birch Plywood

Classification of Alumina Ceramic

lioasaigon.vn

Three Phase Power Transformer

Transformer Box

Z Bracket Mounting Small Corner Braces Stainless Steel A2 L Shape Shelf Flat Angle Bracket

Propane Gas Line

zeroboard4.asapro.com

Anodized Aluminum Middle Clamp for Solar Power System

Aluminum Stand Seam Roof Clamp Solar Lock Solar Clip

Pesticide Formulation Auxiliary

What are the differences between Surgical Masks and Medical Masks

What is the difference between the notebook cover

Trisiloxane

Several fields of computerized flat knitting machines are often used

Automatic Hospital Sliding Door

http://www.jazzmouth.org

Buried Copper Coin PCB

OTHERS

EM-528K Rigid-Flex PCB

Battery for ipad

http://www.tongiljuryu.co.kr

ELIC Rigid-Flex PCB

Usb C To Usb Cable

Aluminum Stamping Press

Woltman Flange Hot Water Meter

abilitytrainer.cloud

Electric Parts Stamping Press

Woltmann Removable Cold Water Meter

Metal Punch Press Machine

Horizontal Woltmann Cold Water Meter

Eye Screw Din 580

Hybrid Solar System Lebanon

Lifepo4 100ah

intouch.com.tn

Eye Screw JIS 1168

Eye Screw Bs4278l Long Shank Collared Eyebolt

Solar Home Lighting System

plot28.com

Class10 Square Weld Nut

Brass Square Nut

Hot Food Container

Carbon Steel Square Weld Nut Type 1C Plain

Paper Boxes With Lids

Eye shadow box

Hooks

Hotel Bath Towel

Thimbles

sudexspertpro.ru

Solid Pillow Case

Swivels

100% Cotton Bed Sheet

Polyester Fiber Wadding

2.4GHz 30W Anti Drone Signal Jammer Module

pgusa.tmweb.ru

5.8G 50w Anti Drone Signal Jammer Module

Hospital Heat Pad

5.8G 100W High Power Anti Drone Signal Jammer Module

Ziplock Bag With Design

Auto Parts Mold Everything You Need to Know

Water Sport Bottle

What is the basic knowledge of LED Warning Lights

Bpa Free Water Bottle

Stainless Steel Beer Mug

What is different about industrial sewing machine

mobileretail.chegal.org.ua

Unique Candle Tins

Type of Cable Lug

Candy Tin Packaging

sakushinsc.com

Types of Automotive Sensors

yhxbcp000398 Front Brake Pad

Small Candy Tin

100a 2 Pole Isolator Switch

3d Building Modeling

3d Building Rendering Quotes

3 Storey Building Structural Design Render

SPD Surge protector

http://www.issasharp.net

110V 63A Manual Transfer Switch

If you would like to grow your know-how only keep visiting this web

site and be updated with the latest information posted here.

Aluminum Sheet Metal Stamping Bending Parts

http://www.speelmrgreen.nl

High Reach Forklift

Smart Glass Cleaner Robotic

Coating Hardware Stamping Parts Metal Fabrication

Excavator Attachments

Stamping Sheet Part Stainless Steel Aluminum

Polythene Extruder Machine

Energy Composite Power Line Poles

Hdpe Pipe Extruder Machine

Hdpe Pipe Extruder Machine

Utility Poles with FRP Composite Poles

modecosa.com

40 Ft Fiberglass Poles

SGCC Galvalume Coil

Single Bowl Sink

Stainless Steel Sink Bowl

SGCH SECD SECE Galvanized Square Tube

me.mondomainegratuit.com

Double Sink Top

SECC Galvanized Square Tube

polioftalmica.it

Kids Mid Sleeper Bed

Stock Equipment

Wicker Pet Bed

Belling Equipement

Furniture

Adjustable Calibration Sleeve Technology

Flush Socket

ASTM F436 Hardened Steel HDG Flat Washer M14

hanillab.co.kr

ASTM F436 Hot Dip Galvainzed Carbon Steel High Tensile Large Flat Washer

Button Switch

DIN9021 HDG Carbon Steel Large Flat Washer

British Sockets

Engagement Ring Box

http://www.jdsd.co.jp

Stainless Steel 304 Socket Head Cap Screw Bolt Allen Inner Self Tapping Screw

304 Stainless Steel M6 Half Round Head Plum Blossom Self Tapping Screw And Bolt

Jewellery Travel Organiser

Ss304 Ss316 Pan Head Cross Self-Tapping Phillips Full Thread

Rings Case

DIN582 A2-70 SS304 Stainless Steel Lifting Eye Nuts M24 M36

M8 Stainless Steel 18-8 DIN582 Lifting Eye Nut

procure.contitouch.co.zw

DIN582 Stainless Steel A2 Eye Nut M8

Machine Paint

Helmet Spray Paint Machine

Panel Spraying Machine

Stainless Steel A2 A4 410 Solar Mounting Solar Panel Hanger Bolt For Metal

Fiber Optic Home Network

Fiber Optic Fiber

Drop Fiber

M10x200mm SS304 Metal Roof PV System Double Head Hanger Bolt For Solar Mounting

alajlangroup.com

Stainless Steel 304 316 M6-M10 Double Threaded Hanger Bolt for Solar System

I couldn’t agree more with the insightful points you’ve articulated in this article. Your profound knowledge on the subject is evident, and your unique perspective adds an invaluable dimension to the discourse. This is a must-read for anyone interested in this topic.

I can’t help but be impressed by the way you break down complex concepts into easy-to-digest information. Your writing style is not only informative but also engaging, which makes the learning experience enjoyable and memorable. It’s evident that you have a passion for sharing your knowledge, and I’m grateful for that.

Jetta Fuel Pump 1989-1992

samogon82.ru

Metal Marking Machine

Fiber Marking Laser Machine

2d 3d Crystal Photo Machine

Toledo Fuel Pump 1992-1996

Golf Fuel Pump 1989-1992

car.thinksmall.vn

Passat CC Fuel Pump 2009-2017

Big Roll Of Aluminum Foil

Silver Foil Container

Round Aluminum Tray

Crafter Fuel Pump 2006-2016

Crafter Fuel Pump 2012-2016

What are the Fabrics of Camping Tent

http://www.modan1.app

Features of Stainless Steel Coil

5 Gallon Mylar

Spout Pouch Bag

Custom Shaped Mylar Bag

PCB Pure Sine Wave Power Inverter Circuit Board

Features of Sand and Gravel Separator

The origin of jigsaw puzzles

Large Room Air Purifier

soonjung.net

What material is generally used for the LED tube housing

High Temperature Air Filters 250℃

Aluminum Frame Pre Air Filters

I’ve discovered a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your unwavering dedication to offering trustworthy information is truly commendable. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I deeply appreciate your consistent reliability.

Your positivity and enthusiasm are truly infectious! This article brightened my day and left me feeling inspired. Thank you for sharing your uplifting message and spreading positivity to your readers.

Auto Wheel Bearing Kits VKBA3298

Four Rack Tackle Case

http://www.pstz.org.pl

Hth 6 In 1 Chlorine Tablets

Round Flower and Plant Bamboo Fiber Flower Pots

Zephiran Chloride

All Clear Chlorine Tablets

116570 79466Someone essentially assist to make severely posts I may state. That could be the really very first time I frequented your site page and so far? I surprised with the analysis you produced to create this certain submit incredible. Magnificent task! 692230

large power relay

Scomi Oil Shale Shaker Screen

http://www.evosports.kr

How to maintain aluminum alloy doors and windows

Swaco Mamut Steel Frame Screen

What is the use of the backup protection switch of the surge protector

Other SCREEN MOD EL

Helical Coil Spring

16B High Structure Heavy Duty Connector Housings

portal.knf.kz

The poroblem that should pay attention to when installing Anti insect Net

1mm Diameter Spring

Garage Tension Springs

RPET NW BAG

22mm Built In Hall Brushless Gear Motor For Household

http://www.gbwhatsapp.apkue.com

Wire Basket Wood Top

A Diaper Bag

12V/24V RC555 High Torque Micro Brushed DC Motor

37mm BLDC Gear Motor For Salt Therapy

Desktop Box Organizer

Expanded PTFE Products

Bearing Wear Strip Tape

Cute Backpacks

http://www.hunin-diary.com

Sealing Machine Equipment

Cooler Bag

Computer Backpack

Wall Cladding Aluminium Panel Sheet

Pressure control principle of Vacuum Coating Machines

hcaster.co.kr

Solid Aluminum Plate

Astm B209 Alloy 3003 Temper H14

What is the function of Portable Zinc Alloy Metal Handled Massage

320w Polycrystalline Solar PV

http://www.yoomp.atari.pl

25% Carbon Fiber Filled PTFE Rod

25% Glass Fiber Filled PTFE Rod

30×30 Tarp

Army Tarp

15% Graphite Filled PTFE Teflon Rod Bar

Blockout Fabric

Air Brake Valve

misiniec.pl

Truck Starter Relay

220KV and Below Modular Intelligent Prefabricated Substations

Right Tie Rod End

GCK Low Voltage Withdrawable Switchgear

American Type Prefabrication Substation

Air Circuit Breaker

Air Dryer Assy

Prefabricated Box Substation

Mercedes Benz Pump

chungsol.co.jp

EAS AM Deactivator

EAS Multifunctional Magnetic Detacher

EAS Golf Tag Detacher

EAS RF Deactivator

Trivalent Chromium

Matt Chrome Electroplating On Plastic

EAS Detacher for Pencil Tag

Plastic Chroming

Chrome Bezel

Abs Chrome Plating Cover Steamer (Grz) For Coffee Machine

Mini Fridge For Bedroom

Baby Diaper Plastic Packaging Bag

Electric Stand Mixer

kawai-kanyu.com.hk

Plastic Baby Diapers Packaging Bag

Disposable Baby Diaper Packaging Bags

Electric Food Mixer For Baking

Patisserie Display Units

Side Gusset Baby Diaper Packaging Bags

Commercial Stand Mixer

Heat Seal Diaper Plastic Packaging Bag

Necklace Case

Baby Nappy Packing Bags

Plastic Diapers Package Bags

Plastic Jewellery Box

Personalised Jewellery Box

dtmx.pl

Gift Sets

Baby Nappy Packaging Bags

Baby Nappy Package Bags

Travel Jewelry Organizer

Jewellery Organiser Box

Conveyor belt series

Perforated Metal Sheet

Balcony Privacy Screen Cover Balcony Shield Screens Net

Knitted Wire Mesh

reminders.chegal.org.ua

Wire mesh deep processing series

HDPE Triangle Sun Protection UV Shade Sail for Balcony

Privacy Fence Screen Heavy Duty Windscreen Fencing Mesh

Peforated metal mesh series

HDPE Garden Windscreen Netting Privacy Screen Net

Outdoor Garden Balcony Privacy Screen

This article is a real game-changer! Your practical tips and well-thought-out suggestions are incredibly valuable. I can’t wait to put them into action. Thank you for not only sharing your expertise but also making it accessible and easy to implement.

Forged Alloy Wheels

Brass Bronze Parts

Fishing Rod Holder

Marine Ladder

Forged Aluminum Wheels

Marine Steering Wheel

Monoblock Wheels

Copper Plated Marine Hardware

procure.contitouch.co.zw

5×120 Forged Wheels

Forge Auto Wheels

Printing Spout Pouch For Fruit Junit

http://www.tdzyme.com

Air Cooler Fan Fan

Ipc Power Supply Fan

Liquid Lotion Beauty Spout Pouch

150x150x50mm Fan

Plastic Packaging Cosmetic Spout Pouch

Silent Fan

Stand Up Plastic Packaging Bag With Spout

Stand Up Spout Pouch For Liquid

Intelligent Watering Flowerpot Fan

Portable Small Electrical 11kv Substation

11 415 kv air insulated ais mini substation

Tpt Solar Backsheet

Prismatic Tempered Glass For Solar Panel

33kv 11kv Medium Voltage Padmount Substation

Solar Panel Low Iron Temper Glass

11kv Miniature Distribution Substation

Arc Solar Glass

11kv Mv Solar Power Package Substation

Junction Box Ip68 Solar Panel

fpmontserratroig.cat

3kv Solar System

hexaxis.ru

Bottle Sleeve POF Shrink Wrap

Bottle POF Shrink Wrap

8kva Solar System

Low MOQ POF Shrink Wrap

Cans POF Shrink Wrap

Tubular POF Shrink Wrap

Solar Energy Unit

600w Solar Panel Price

Solar Energy Installation Cost

Metal Button Switch Industrial Equipment Connection Harness

Solar Water Heater Function

Smart Bms For Lithium Ion Battery

Lithium Phosphate

Solar Battery System

http://www.dtmx.pl

Internal Power Supply Industrial Equipment Connection Harness

Shockproof Foam Industrial Equipment Connection Harness

DB25 Industrial Equipment Signal Transmission Harness

Industrial Equipment Aerial Docking Connection Harness

Lcd Panel

Fine Blank Stamping Parts

Bicycle Parts Stamping Parts

Aluminum Parts Housing

http://www.xrpro.or.kr

Aluminum Alloy Shell

Wiper Stamping Parts

High Precision Metal Stamping Parts

Heat Sink Extruded Waterproof Pcb CNC Enclosure Box

Aluminum Lampshade

Aluminum Alloy Charging Pole Housing

Aluminum Profile Shell

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

Aluminum 3003

Aluminium Bike Frame

Sheet Aluminum

Home Slippers For Kids

Winter Slippers For Kids

cci1.designpixel.or.kr

Aluminum Suppliers

Boy House Slipper

Aluminum 2024

Boy House Slipper 1

Winter Warm House Slippers

Ceramic Substrates

Protonitazene Hydrochloride

Plain Substrates

2-Iodo-1-P-Tolyl-Propan-1-One

Igniter of Exhaust Gas Aftertreatment Device

Parking Heater and Other Parts

Tiletamine Hydrochloride

Heating Elements of Electric Car

http://www.terapiasinfronteras.com

Dimethocaine Hydrochloride

7-Keto-Dehydroepiandrosterone

Your dedication to sharing knowledge is unmistakable, and your writing style is captivating. Your articles are a pleasure to read, and I consistently come away feeling enriched. Thank you for being a dependable source of inspiration and information.

I’ve discovered a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your unwavering dedication to offering trustworthy information is truly commendable. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I deeply appreciate your consistent reliability.

N-(9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)-D-phenylalanine

1-20L Semi-Automatic Filling Machine

Pharmaceutical Chemicals Good Quality Best Price China Factory Supply CAS 35661-60-0 Fmoc-Leu-Oh

Fmoc-Phe-Oh

borisevo.ru

Fmoc-L-Alpha-Alanine

1-5L Fully Automatic Filling Machine

20-50L Semi-Automatic Filling Machine

200L IBC Visual Fully Automatic Filling Machine

Fmoc-Ala-Oh

200L 1000L Visual Fully Automatic Filling Machine

Croissant automatico

Marmellata di pesce economica

Silver Diamond Red Wine Decanter

del commestibile

Skull-shaped Rotatable Glass Wine Bottle

mxixray.com

Snow Mountain Style Crystal Red Wine Decanter

Produttore di pane italiano

Double Wall Glass Beer Mug

Tagliabordo per scatole di cartone

Hammered Glass Teapot

I’m genuinely impressed by how effortlessly you distill intricate concepts into easily digestible information. Your writing style not only imparts knowledge but also engages the reader, making the learning experience both enjoyable and memorable. Your passion for sharing your expertise shines through, and for that, I’m deeply grateful.

I’ve found a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your dedication to providing trustworthy information is something to admire. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I appreciate your consistent reliability.

Si3n4 Plate

Spring Hanger Bracket Mounting

Truck Helper Spring Bracket

Trailer Leaf Spring Hanger Bracket

Silicon Nitride Si3n4 Ceramic Substrate

xrpro.or.kr

Silicon Rich Nitride Tiles

Ceramic Insulating Heat Dissipation Substrates

Scania 1528326

Metal Ceramic Substrates

Nissan Truck Parts Spring Hanger

http://www.jdsd.co.jp

Portable Charger 100w

Ac Solar Panel

Portable Solar Charger 100w

Wind Solar Hybrid System

economy

Current Transformer

100 Watt Solar Charger for Camping

Energy Storage Battery

Watt Solar Charger for Camping

easy maintenance

LSR Molding

LSR Molding

LSR Infant Molding

Cork Bag

Aux Switch Panel

Fast Charger Car Charger

General Switch Panel

Auto Fuse Block

LSR Molding for Medication

raskroy.ru

Automotive Switch Panel

MB Abrasive

Multifunctional Spring Rod

raskroy.ru

Multifunctional Knife Pliers

Diamond Squaring Wheel For Ceramic Tile

Military Shovel

Keda Squaring Wheel

Glaze Polish Grinding Block

Self-Defense Spring Stick

Abrasive For Ceramic Tile

Telescopic Swing Stick

Nordic Simple Mountain View Glass Kettle

Low Speed Diesel Engine

Retro Embossed Gold-Rimmed Glass Kettle

Pineapple Pattern Glass Cold Kettle

Hand Brewed Glass Coffee Pot

Retaining Ring

Glacier Pattern Glass Cold Water Bottle

Main Bearing

Self-Locking

Exhaust Valve Upper Parts

http://www.optselmash.myjino.ru

Green Tea Gunpowder 9375

gpsmarker.ru

Green Tea Gunpowder 9475

Green Tea Gunpowder Tea Dl022

Absorption Dynamometer

Vehicle Testing Equipment

Green Tea Gunpowder Tea 2378

Atv Dyno

Men Shavers

Inspection Lane

Green tea gunpowder tea 9105

Your unique approach to addressing challenging subjects is like a breath of fresh air. Your articles stand out with their clarity and grace, making them a pure joy to read. Your blog has now become my go-to source for insightful content.

Your enthusiasm for the subject matter shines through in every word of this article. It’s infectious! Your dedication to delivering valuable insights is greatly appreciated, and I’m looking forward to more of your captivating content. Keep up the excellent work!

Paper Boxes

Gift Bags

Lpg Pd Meters

Total Control Systems Meter

Rotary Displacement Meter

Fmc Pd Meters

Heavy Duty Tube Clamp

http://www.imar.com.pl

Paper Bags

Kraft Bags

Luxury Bags

Pretty part of content. I simply stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital

to say that I acquire in fact loved account your weblog posts.

Any way I’ll be subscribing for your feeds or even I fulfillment you get admission to consistently quickly.

Ceramic Decor Vase

Table Calendars

Souvenir Paper Bags

Paper Wine Bottle Bags

Shopping Bags with Ribbon Handles

Large Ceramic Pots

Electroplate Vase

Ceramic Flowerpot

Goodie Bag Paper Bag

http://www.apkue.com

Ceramic Home Decoration

V-Plow Diverter

Marble Mosaic Kitchen Backsplash

Copper Bunching Machine

Friction Flat Self Aligning Idler Bracket

Round Marble Mosaic Tile

Tile Mosaic Behind Stove

Mosaic Tile And Stone

Taper Self Aligning Idler Bracket

Double Sealed Conveyor Transfer Chute

Side Plow Diverter

licom.xsrv.jp

Your writing style effortlessly draws me in, and I find it nearly impossible to stop reading until I’ve reached the end of your articles. Your ability to make complex subjects engaging is indeed a rare gift. Thank you for sharing your expertise!

Your blog is a true gem in the vast expanse of the online world. Your consistent delivery of high-quality content is truly commendable. Thank you for consistently going above and beyond in providing valuable insights. Keep up the fantastic work!

Your blog has rapidly become my trusted source of inspiration and knowledge. I genuinely appreciate the effort you invest in crafting each article. Your dedication to delivering high-quality content is apparent, and I eagerly await every new post.

I’ve discovered a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your unwavering dedication to offering trustworthy information is truly commendable. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I deeply appreciate your consistent reliability.

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

PP Nonwoven Fabric

Luxury Customized Lighting

Home Customized Light

http://www.sudexspertpro.ru

High Bright Indoor Chandelier

Solar Landscape Waterproof Pathway Footpath Lights

Warm pathway lights sets

Classic Interior Chandelier

Solar Pathway Lights Outdoor

Waterproof Sideways Duracell Solar Pathway Lights

Classic LED Lighting

Your dedication to sharing knowledge is unmistakable, and your writing style is captivating. Your articles are a pleasure to read, and I consistently come away feeling enriched. Thank you for being a dependable source of inspiration and information.

I’m genuinely impressed by how effortlessly you distill intricate concepts into easily digestible information. Your writing style not only imparts knowledge but also engages the reader, making the learning experience both enjoyable and memorable. Your passion for sharing your expertise shines through, and for that, I’m deeply grateful.

Paper Pulp Tray Packaging

roody.jp

AC Power Tools

Solenoid Spray Gun

PAC

AC Power Tools

LSR Seal Ring for Automotive Connectors

Alum Coagulant Formula

Aluminum Sulfite Molar Mass

Paper Material

HVLP Spray Gun

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

Trenbolone Acetate

Cas 859-18-7

Green Tea Gunpowder Tea

Metric Ratcheting Spanner Set

1165910-22-4

Ks-0037

Green Tea Chunmee Tea

Double Offset Box End Ratcheting Wrench Set

Larocaine

mdjspb.ru

Green Tea Gunpowder Tea

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

Your positivity and enthusiasm are undeniably contagious! This article brightened my day and left me feeling inspired. Thank you for sharing your uplifting message and spreading positivity among your readers.

Shoe Eyelet Machine

PTFE Color Filament Yarn

Electric Curtain Eyelet Punch Machine

PVDF Multifilament

PTFE Filament Yarn

Grommet Machine For Banner

Pneumatic Eyelet Machine

PVDF Monofilament

titanium.tours

High Strength PTFE Filament Yarn

40mm Eyelet Machine

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

Your blog is a true gem in the vast expanse of the online world. Your consistent delivery of high-quality content is truly commendable. Thank you for consistently going above and beyond in providing valuable insights. Keep up the fantastic work!

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

Non-Woven Ultrasonic Bags

Stainless Steel Pipeline Water Dispenser

Biodegradable Bag

Aerator Fish Pond

Pond Aerator

PLA Non Woven Bag

Vest Bag

Paddle Wheel Aerator 0.75 Kw

2hp Paddle Wheel Aerator Ponds

Paddle Wheel Aerator Bearing Supporter

http://www.abilitytrainer.cloud

Your enthusiasm for the subject matter radiates through every word of this article; it’s contagious! Your commitment to delivering valuable insights is greatly valued, and I eagerly anticipate more of your captivating content. Keep up the exceptional work!

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

This article is a true game-changer! Your practical tips and well-thought-out suggestions hold incredible value. I’m eagerly anticipating implementing them. Thank you not only for sharing your expertise but also for making it accessible and easy to apply.

I wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude for the wealth of invaluable information you consistently provide in your articles. Your blog has become my go-to resource, and I consistently emerge with new knowledge and fresh perspectives. I’m eagerly looking forward to continuing my learning journey through your future posts.

I just wanted to express how much I’ve learned from this article. Your meticulous research and clear explanations make the information accessible to all readers. It’s evident that you’re dedicated to providing valuable content.

Your dedication to sharing knowledge is unmistakable, and your writing style is captivating. Your articles are a pleasure to read, and I consistently come away feeling enriched. Thank you for being a dependable source of inspiration and information.

Your passion and dedication to your craft radiate through every article. Your positive energy is infectious, and it’s evident that you genuinely care about your readers’ experience. Your blog brightens my day!

I just wanted to express how much I’ve learned from this article. Your meticulous research and clear explanations make the information accessible to all readers. It’s evident that you’re dedicated to providing valuable content.

Your writing style effortlessly draws me in, and I find it nearly impossible to stop reading until I’ve reached the end of your articles. Your ability to make complex subjects engaging is indeed a rare gift. Thank you for sharing your expertise!

In a world where trustworthy information is more crucial than ever, your dedication to research and the provision of reliable content is truly commendable. Your commitment to accuracy and transparency shines through in every post. Thank you for being a beacon of reliability in the online realm.

I’ve discovered a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your unwavering dedication to offering trustworthy information is truly commendable. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I deeply appreciate your consistent reliability.

Your positivity and enthusiasm are undeniably contagious! This article brightened my day and left me feeling inspired. Thank you for sharing your uplifting message and spreading positivity among your readers.

Stainless Steel Grinder

edi.chegal.org.ua

Stainless Steel Grinder

Stainless Steel Grinder

zsbh21 wing open truck rear door hinge

zsbh25s refrigerated truck door hinge

Weed Container Smell Proof

zsbh20 truck rear door hinge

zsbh26s refrigerated truck door hinge

Tobacco Tray

zsbh18 rear truck door hinge

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to connect with your audience emotionally is commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

I’ve discovered a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your unwavering dedication to offering trustworthy information is truly commendable. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I deeply appreciate your consistent reliability.

I’m genuinely impressed by how effortlessly you distill intricate concepts into easily digestible information. Your writing style not only imparts knowledge but also engages the reader, making the learning experience both enjoyable and memorable. Your passion for sharing your expertise is unmistakable, and for that, I am deeply appreciative.

I’d like to express my heartfelt appreciation for this enlightening article. Your distinct perspective and meticulously researched content bring a fresh depth to the subject matter. It’s evident that you’ve invested a great deal of thought into this, and your ability to articulate complex ideas in such a clear and comprehensible manner is truly commendable. Thank you for generously sharing your knowledge and making the process of learning so enjoyable.

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

Your storytelling prowess is nothing short of extraordinary. Reading this article felt like embarking on an adventure of its own. The vivid descriptions and engaging narrative transported me, and I eagerly await to see where your next story takes us. Thank you for sharing your experiences in such a captivating manner.

This article is a true game-changer! Your practical tips and well-thought-out suggestions hold incredible value. I’m eagerly anticipating implementing them. Thank you not only for sharing your expertise but also for making it accessible and easy to apply.

zscra04 aluminium alloy side rail rubber water repellent strip

Expansion Joint Flange Type

zscra03 truck curtain aluminium profile rail

alphacut.jp

zscra02 curtain track rail side curtain rod straight guide

Rubber Pipe Coupling

zscra06 truck aluminium profile curtain pole

Plumbing Elbow

Reducing Tee

Flexible Tap Connectors

zsjb05 square tube jack bar

Round Neck Cosy Cashmere Jumper

Smart Led Bathroom Mirror

Wall Attached Makeup Mirror

Cropped Round Neck Cosy Cashmere Jumper

toyotavinh.vn

Led Mirror

Wall Mounted Illuminated Makeup Mirror

Cashmere Blend Wide Round Neck Jumper

Mirror Light For Wash Basin

Round Neck Cashmere Sleeveless Jumper

Round Neck Argyle Cashmere Jumper

SightCare supports overall eye health, enhances vision, and protects against oxidative stress. Take control of your eye health and enjoy the benefits of clear and vibrant eyesight with Sight Care. https://sightcarebuynow.us/

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

I’m genuinely impressed by how effortlessly you distill intricate concepts into easily digestible information. Your writing style not only imparts knowledge but also engages the reader, making the learning experience both enjoyable and memorable. Your passion for sharing your expertise is unmistakable, and for that, I am deeply appreciative.

Your writing style effortlessly draws me in, and I find it difficult to stop reading until I reach the end of your articles. Your ability to make complex subjects engaging is a true gift. Thank you for sharing your expertise!

20W Constant Current 0-10V Dimmable LED Driver

250W Constant Voltage Triac Dimmable LED Driver

Galvanized Scaffolding

Adjustable Base Jack

150W Constant Voltage Triac Dimmable LED Driver

Scaffolding Contractors

http://www.borisevo.ru

100W Constant Voltage Triac Dimmable LED Driver

H Frame Scaffolding

14W Constant Current 0-10V Dimmable LED Driver

Sleeve Coupler Scaffolding

18W Wall Mounted Power Adapter

Street Lamp

http://www.jion.co.jp

Ufo Highbay Led Industrial

Outdoor Tennis Lighting

12W Wall Mounted Power Adapter

Outdoor Led Flood Light

240W PD Quick Charger

5W Wall Mounted Power Adapter

Led Stadium Light

200W PD Quick Charger

Your enthusiasm for the subject matter radiates through every word of this article; it’s contagious! Your commitment to delivering valuable insights is greatly valued, and I eagerly anticipate more of your captivating content. Keep up the exceptional work!

Your passion and dedication to your craft radiate through every article. Your positive energy is infectious, and it’s evident that you genuinely care about your readers’ experience. Your blog brightens my day!

I wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude for the wealth of invaluable information you consistently provide in your articles. Your blog has become my go-to resource, and I consistently emerge with new knowledge and fresh perspectives. I’m eagerly looking forward to continuing my learning journey through your future posts.

Swing Arm Table Lamp

Classic Swing Table Lamp For study

Tungsten Carbide Endmill

Led Long Swing Arm Adjustable Classic Desk Lamp

Wood Carving Drill

Three-tone light table lamp

Woodworking Auger Bits

Wood Forstner Bit

http://www.stickers.by

Black Study Table lamp Office Desk Light

Wood Drill Bit

Avant-Garde Tripod Floor Beacon

Nuclear Protection Suit

Fashionable Tripod Floor Lantern

CE Certification Nuclear Radiation Survey Meter

CE Certification Mobile Radiation Meter

Stylish Tripod Lighting Ensemble

http://www.naimono.co.jp

Sleek Tripod Illumination

Best Mobile Radiation Meter

Latest Design Three-Legged Lamp

Best Nuclear Reactor Instrumentation

worksp.sakura.ne.jp

Crab Puff Pastry Bites

Fast Food Salads

Hand Hold Servo Motor Screwdriver

Intelligent Cordless Screwdriver

Crab Leg Surimi

High Torque Smart Electric Screwdriver

Imitation Crab Nutrition Label

High Torque Smart Screwdriver

Fast Food Salads

In-Line Torque Smart Electric Screwdriver

Current Controlled Handheld Screwdriver

Servo Smart Electric Screwdriver

Reflective Sheeting Manufacturers

Reflective Saftey Tape

Reflective Sheeting China

Electric Torque Screwdriver

Reflective Vest

Handheld 90° Smart Screwdriver

Reflective Vest Custom

Screwdriver With Smart Controller

duhockorea.net

Your enthusiasm for the subject matter radiates through every word of this article; it’s contagious! Your commitment to delivering valuable insights is greatly valued, and I eagerly anticipate more of your captivating content. Keep up the exceptional work!

Your writing is so refreshing and authentic It’s like having a conversation with a good friend Thank you for opening up and sharing your heart with us